Dissent and Accord: Buddhism's First Schools After Buddha

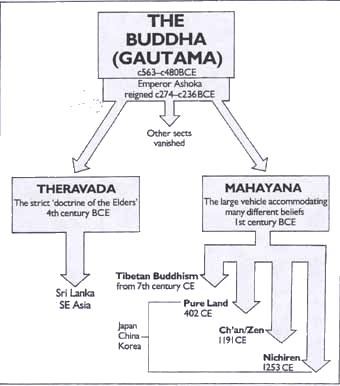

Buddhism began in a way that was easily accessible, through Buddha's storytelling and teachings from his mouth to his followers' ears. Buddha's followers needed only to listen to the stories that they were being told, then apply the lessons of those stories to their everyday lives. Of course Buddha was a master storyteller who inspired a great many followers. Following Buddha's death in the early fifth century BCE, several Buddhist traditions flourished. Of these traditions, only Theravada Buddhism and Mahayana Buddhism, sharers of the basic concepts of the Four Noble Truths and the Eightfold Path, survived with any strength and prevalence. However, this was not something that developed easily or without consternation and disagreement, and it took from Buddha's death until 80 BCE for the schools to converge and reach some sort of consensus at the Great Council and then reach an accommodating eventual coexistence: "The old Hindu ways were making a strong comeback, challenging Buddhism. And the Buddhists themselves were separating into their own schools of teaching, quarreling among themselves. In other words, it was a time of trouble for the Buddhists. Undoubtedly. there was a yearning in the hearts of many to reestablish order and orthodoxy. That was the climate out of which grew the call for the Great Council." (Bresnan, 251)

One of the goals of the Great Council was to bring scriptural form to Buddha's storytelling and teachings, the permanence of written form that could be lacking in the oral tradition carried down from one generation to the next. The leading school and great effort to bring scriptural form to the initial oral tradition, its organization and culmination, came to be known as Theravada, the outcome of which was the Pali Canon. What then, was the form of The Pali Canon, and what ultimately is its meaning and purpose to us? It took form in three separate book collections or "baskets", one for each category: the suttas, which were essentially transcripts of the exact words of Buddha's first oral teachings; the vinaya, which set down the rules and organizational structure for members of the Orders to follow in their everyday lives; and finally the abhidhamma, essays and works collected over the several centuries since Buddha's death, collectively the wisdom gathered from the philosophies most profoundly expressed by Buddha's followers. The first two categories purported to come directly from Buddha's teachings, while the third category was from how Buddha's students interpreted and applied those teachings. The vinaya give the most practical guidelines for how to achieve nirvana: "Thus, all of the rules of the Buddhist monastic Orders were directed at helping each member do the best possible effort that he or she could in becoming a living expression of the Eightfold Path. The rules of vinaya were designed to keep the traveler on the path." (Bresnan, 253)

Was there still room for dissent to support different schools of Buddhism after the rise of Theravada and the creation of the Pali Canon? Yes, despite the prevalence of Theravada Buddhism giving rise to the Pali Canon, there were still dissenters who objected to how narrowly the vinaya offered the Middle Path and true nirvana only to those in the monastic orders: "It seemed that the only genuine Buddhists were the members of the monastic orders; the laity played hardly any part at all. Buddha, though, had directed his teaching to everyone, not just a select few." (Bresnan, 263) The dissenters created a new metaphor for a different approach to Buddhism. The narrow path of the Theravada and its monastic orders equaled a small boat, a hina-yana compared to the much more populist maha-yana, the large boat with enough room for everyone. Thus the Mahayana school claimed a different set of scriptures that also originated from Buddha's oral teachings that somehow missed inclusion on the Pali Canon. "Mahayanists responded to attacks on the veracity of their sutras by arguing that...they had been passed directly by Buddha to some specially chosen disciples...they had been most carefully preserved in memory and passed along from generation to generation in the grand oral tradition." (Bresnan, 265) Among the Mahayanan sutras was the proclamation that any man or woman, not just monks, can achieve Buddha-hood. The eventual ultimate metaphor for these two schools was not in the form of boats but in the form of of a wheel, borrowing a concept from "British Buddhologist Christmas Humphreys: "Theravada is the hub of the wheel-solid, essential, at the core. Mahayana is represented by the many spokes of the wheel, a full circle of variations, but all having their source in the hub." (Bresnan, 268) Humphreys has written some fascinating works on Buddhism, among them "The Twelve Principles of Buddhism":

https://donsnotes.com/religion/buddhism/index.htmlWorks Cited

Bresnan, Patrick S. Awakening, An Introduction to the History of Eastern Thought. Routledge 2018

Don's Notes website, https://donsnotes.com/religion/buddhism/index.html, Accessed 22 March 2022

Vajratool website, https://vajratool.wordpress.com/2010/05/05/christmas-humphreys-the-most-eminent-of-20th-century-british-buddhists/, Accessed 22 March 2022

Comments

Post a Comment